Violation and Making The Road By Walking It by Zoë Flowers

/Content Notice: The purpose of the #LoveWITHAccountability forum on The Feminist Wire and project is to prioritize child sexual abuse, healing, and justice in national dialogues and work on racial justice and gender-based violence. Several of the featured articles in this forum give an in-depth and, at times, graphic examination of rape, molestation, and other forms of sexual harm against diasporic Black children through the experiences and work of survivors and advocates. The articles also offer visions and strategies for how we can humanely move towards co-creating a world without violence. Please take care of yourself while reading.

By Zoë Flowers

“Those were my favorite shorts. Blue with a white strip down the side”

One: Violation

When I was a little girl, my grandparents’ house was like a castle. It was a Victorian style home with many oddly shaped rooms. Because my parents worked, they would send me to my grandmother’s house every summer. I spent most of my time either reading or playing in the backyard.

My grandmother’s backyard was massive. It had huge oak trees and wildflowers that grew in all directions. It was my magical kingdom. My older cousins hated getting dirty; so, I had the yard all to myself. It was just me, the ladybugs, and the frogs. On hot days, I’d run through the sprinkler, and then collapse on the dirt, letting the sun beat down on my drenched body.

After a while, I’d reluctantly return to the house damp and covered in dirt.

Nighttime was the only time my cousins and I played together. We would play hide and seek, truth or dare, anything we weren’t supposed to do. As soon as my grandmother went to bed, we’d go out and play.

My grandmother was not as strict as my parents were. Her main restriction was on laziness and boredom. I’m from a traditional West Indian family that firmly believed that idle hands were the devil’s playground. Laziness was a trait she would not tolerate and was reason enough for a swat across the legs. In her eyes, children had no reason to be bored – ever. If she caught us lying around, she would find something for us to do. There were always dishes to wash, rooms to clean or books to read. That was another good reason for me to stay outside.

Physically, my grandmother was a very attractive woman. People who met her could not believe she had twelve children and sixteen grandchildren because she had such a youthful glow. She had jet-black hair that she wore in a tight bun. At night, she would let it down and I would brush it out for her. It was long and soft. She was a bigged-boned woman who was effortlessly gentle…until she wasn’t. Her dark eyes were often steady and they seemed laser-like when she regaled me with stories about growing up in Jamaica. Her stories were not for my entertainment. They always had some moral that related back to the necessity of being an obedient child. She’d talk/lecture to me for hours while I braided her thick black hair. Still, our ritual was the one chore that I didn’t mind.

Most of my relatives lived very close or visited her often. The house was never empty. Food was always on the stove with grandmother standing over it. She didn’t drink but everyone else in the house did. Liquor was a constant in my family. The adults could always count on getting a drink, a meal and good conversation. There were many nights that I’d sneak out of bed, sit at the top of the stairs and listen to the grown-ups. I loved listening to their loud voices debating, arguing and making fun of one another, often drowning out both the television and stereo. At times, it was difficult to know if they were arguing or joking.

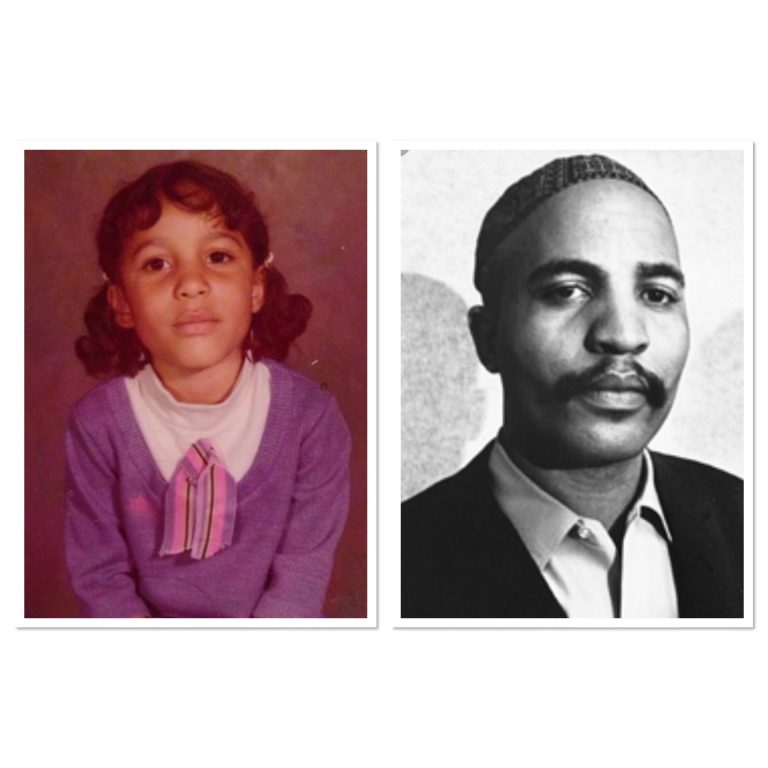

One of my favorite people in that house was my “uncle”. He was different from my other relatives. I could talk to him. No matter what the question, he would answer it honestly. Like my grandmother, my other relatives believed children should be seen and not heard. He wasn’t like that. I thought my uncle knew everything; he’d been to places I’d never even heard of.

He and my “aunt” lived with my grandmother for as long as I could remember. In almost all of their pictures there were exotic women flocked around him. His pictures portrayed a confident young man, tall and muscular with a smooth dark complexion and dark curly hair. I guess he would have been considered attractive in his day, but for as long as I can remember, he’d been old and wrinkled. The only remnant of the young man in the pictures was the mischievous twinkle that never left his eyes.

I was seven years old the first time he fondled me. It was a typical day. It was summer. The adults were in the kitchen laughing and enjoying each other like they always did. He called me in his room. We’d often play checkers or dominoes, which we played to the death. He never let me win; he said it was not good for children, especially women, to get special treatment. I raced up the stairs as I always did. When I got in the room, the board was not in its usual place. I asked him where it was, and he told me it was under the bed. I remember getting down on all fours looking for the game. Suddenly, I felt his fingers frantically tugging at my shorts. They were my favorite shorts. They were blue with a white stripe down the side (Blue has always been my favorite color). They were tight but I loved them so much. I maneuvered myself around and looked at him as he pulled me toward him and clamped his hand over my mouth. I was a chunky kid. The shorts were tight. He was having a hard time getting his fingers in. I didn’t know what was happening. I can’t remember if I knew it was wrong. I can’t remember if I wanted to get away. I just remember him saying, “Shh,” in that raspy voice of his. I remember he was almost smiling. One of his hands stayed on my mouth while he penetrated me with the other. After it was over, I went back downstairs. Everyone was still there. The party hadn’t skipped a bit.

I didn’t remember anything until my early twenties. All the painful memories flooded in on me on an ordinary day. I was driving home….nothing major…then all of a sudden I remembered. I never told my family. I knew they’d believed me but I didn’t think they could handle it. So, like so many other things I kept it to myself. I have not shared this story with anyone….until today.

“The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is – it’s to imagine what is possible.” bell hooks

Two: Making The Road By Walking It

The question of accountability as a radical form of love makes me think about my childhood and how many children of my generation were raised. To me, linking punishment, accountability and love is not a new concept. Many of us were told we were being spanked out of love. And lots of people still believe and enact various forms of punishment to keep children in line “out of love.” So for me, it’s not about people’s inability to make the leap between accountability and love. It’s about whose well-being is valued in our society and whose is not. I can’t talk about transforming societal understanding accountability as a radical form of love until society begins addressing the impact of adult privilege effectively.

To me, accountability would look like no statute of limitations on child sexual assault (CSA) anywhere in the US. As a society, how can we say we care about children and not do everything in our power protect them, their childhood and their right to move unmolested through the world? How we can say they’re our future when many are not safe at home, school, on the sports field, or in church?

Accountability is believing children when they share that they’ve been harmed. It looks like:

- Not re-traumatizing them by forcing them sit at holiday tables with their abuser and acting like that is normal.

- Not giving the girls strategies to “protect” themselves around the known abuser and then praying that the tactics work.

- Acknowledging that boys get raped too.

- Not protecting the abuser because he is a man of color.

- Having difficult conversations with family and friends. I’ve had to have conversations like, “I know he’s your favorite singer etc. but he has a history of x,y&z. Don’t you think that’s a problem? Why would you support him financially?”

Accountability looks like creating environments where children feel safe to disclose. And training for parents on how to deal effectively with them when they do. Accountability looks like communities of color addressing mental and emotional illness from multiple perspectives. When I think about the girl who says her mother’s partner is abusing her and the mother essentially says, “I’m sorry for your loss. I’m staying.” That is a woman that may have been abused. How can we talk to her about holding her partner accountable if she’s been dissociated for years? Will what we’re asking her to do even register? She may even think, “Hell, I got over it. She can too.” Families need mental, emotional and energetic healing to heal patterns like these.

When people come to me for Reiki, they come with all the consequences of a society that prioritizes the needs of adults over children. The trauma of parents who made a decision not to make a decision is lodged in the cells of the people I treat. There are more wounded children masquerading as adults than folks might think. Those “child/adults” then go on to have children of their own and the untreated and unacknowledged family trauma is transmitted right into that unborn child.

Holistic healing practices like Reiki, acupuncture, cupping, yoga and other indigenous technologies are often more effective than traditional healing methods (what are the traditional healing methods? I am confused. Perhaps, I’m using indigenous and traditional synonymously) and need to be more readily available in communities of color. These days I am often invited to “hold space” for large groups of people doing difficult work. This Spring I was called into the Black Women’s Blueprint Truth and Reconciliation Commission where Black survivors shared their stories of abuse for an entire day. This is a step in the right direction and it needs to happen more.

Lastly, I believe that healers need to be more vocal and participatory when it comes to issues like domestic violence and CSA. I believe in “praying and watching.” I also think it’s a good thing for healers to demystify themselves. I think it helps when healers lay themselves bare and let folks know that they’ve dealt with some of the same issues in their own lives.

On the question of justice and can we get it without punitive means.. I never intended to involve law enforcement and the courts in my life. However, my ex-partner’s actions made it impossible not to involve them. They were not helpful in my case. In fact, they were the opposite of helpful. Luckily, my artistic voice and following its wisdom saved my emotional and spiritual life after my experiences with domestic and sexual violence. I gained personal power through books, poetry and theatre. I joined the domestic violence movement and funneled my anger, frustration, and hopes into that work. Then my spiritual nature revealed itself and I followed that to a completely new life as a healing artist. So, in some ways I got non-traditional justice.

That said I recognize that many survivors want their day in court. And they should get that. I know the criminal justice system has major problems. And I’d have no problem seeing it overhauled or dismantled. But I don’t see that happening for a very long time and I do not believe we are in the energetic space where punitive justice is no longer an option. We will know that time has come when the needs of all members of our community are prioritized equitably. That’s the reality I envision and that is the world I am working toward.

Zoë Flowers is an author, poet, actress, Reiki Master and seasoned domestic violence expert. Her poetry and essays can be found in Stand Our Ground; Poems for Trayvon Martin and Marissa Alexander, and Dear Sister: Letters From Survivors of Sexual Assault and several online publications.

With almost sixteen years of experience in the domestic violence field, Zoë has appeared on National Public Radio, works nationally and has spoken internationally on the issue of domestic and sexual violence. Zoë worked at several state domestic violence coalitions where she provided training, technical assistance and expertise to local and state domestic violence programs and community partners across the country.

She was one of the original members of the Black Witch Chronicles (BWC) and shared readings, channeled messages to thousands via Facebook and YouTube as part of the trio. She co-created and co-facilitates Solstice SoulShifting with Dr. G. Love also an original member of BWC. This international retreat provides indigenous healing technologies and survivor-centered healing to folks worldwide.

Her book, From Ashes To Angel’s Dust: A Journey Through Womanhood (formerly called Dirty Laundry: Women of Color Speak Up About Dating & Domestic Violence) emerged from interviews Zoë conducted with survivors of domestic and sexual violence and is set for re-release 2017.ASHES is a ChoreoDrama that uses monologues; poetry and vignettes to breathe life into the original stories shared in From Ashes To Angel’s Dust: A Journey Through Womanhood and includes new stories about racism, same sex violence, body image and the journey to self-love.

Zoë wrote, produces and acts in the powerful ensemble piece, which has had successful performances across the country including, The White House’s United State of Women Summit in Washington, DC on June 15, 2016 and at Yale University’s Fearless Conference on April 9th 2016 as part of Zoë’s presentation entitled, Women of Color, Misogynoir, Sexual Assault & Reclaiming Our Magic, a presentation that she will bring to Smith College in April 2017. Zoë looks forward to returning to Yale in January 2017 where she’ll conduct a four month Campus Community Engagement Project entitled, Becoming Magickal: Exploring Healing Through Womanist Performance. Topics will include: poetry & performance, writing yourself “well” historical oppression, the artist as activist, the magick of trauma and ritual as a healing practice. The project will conclude with a weekend run of ASHES that will be performed by Yale’s Heritage Theatre Ensemble on April 7-8, 2017.