“It Takes A Village”: Afterword to the #LoveWITHAccountability Forum by Aishah Shahidah Simmons

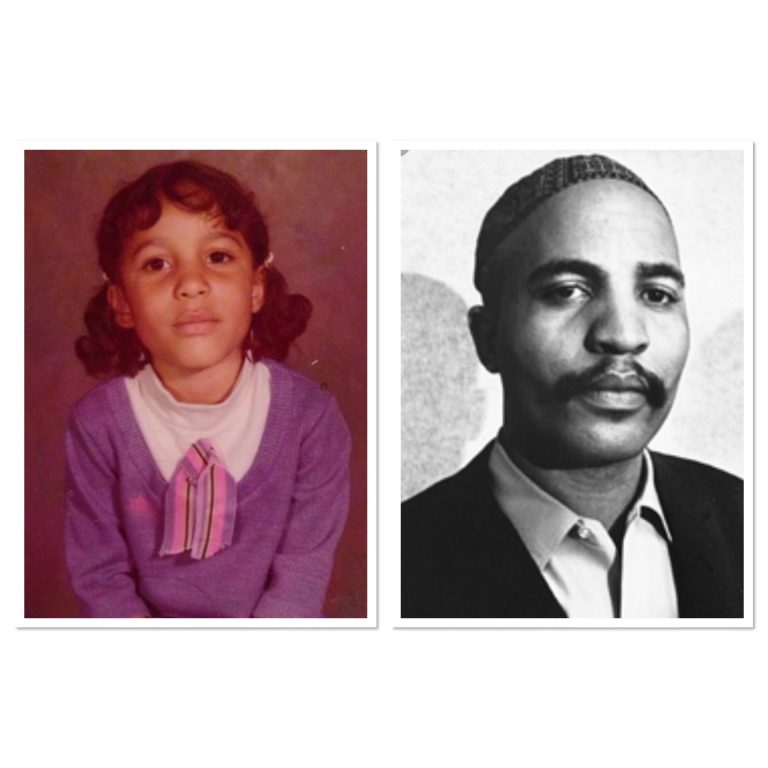

/I had big plans for writing the Afterword to the #LoveWITHAccountability forum, but the truth is I am worn out completely. In the spirit of transparency, I recently became consumed with so much internalized conflict about how my grandfather and also my father would come across in my mother’s courageous contribution to this forum that I couldn’t focus on how I would bring closure to this forum. I, the unapologetic BLACK FEMINIST, was initially unable to fully APPRECIATE that, per my 12th hour invitation to participate, my mother PUBLICLY held herself accountable in this forum. I was more worried that The Feminist Wire readers would think that my Pop-pop was a horrible person. He definitely did horrible things to me as a child but I do not believe he is a horrible person. I didn’t want readers to inquire why I didn’t invite my father to contribute to this forum. He and I are still on the journey. We are not in a place to publicly share about our process. I was still in protection mode.

As a result, I couldn’t accept the invaluable sacred gifts of my mother both privately and publicly articulating the decades long harm inflicted upon me, and deeply heartfelt apologies with meaning. As sister-survivor-comrade Luz Marquez-Benbow wrote in her article, “incest is some insidious sick shit.” The postscript that I wrote at the end of my “mother’s lament” was a brand new development in response to my deep angst. It was not a part of the original plan for this forum. As a result, I do not have the wherewithal to go any deeper right now. My gratitude for my mother pushing herself to get here on her and my journey is endless. I am personally reminded that it is never too late for accountability and healing.

My goal with the #LoveWITHAccountability forum on The Feminist Wire was to create a virtual space to both ignite and also continue dialogues about the taboo topic of child sexual abuse in diasporic Black communities in the wake of all of our heightened awareness about state sanctioned white supremacist violence committed against Black people and our communities. Twenty-nine intergenerational diasporic Black people disclosed and explored child sexual abuse, healing, justice, and love with accountability over a period of ten-days on The Feminist Wire. I’ve only been pregnant once in my life and had an abortion six-eight weeks later. Yet despite my lack of knowledge about carrying a pregnancy to term, I frequently used the analogy of being the thirty-four-week pregnant doula who actively engaged with supporting twenty-eight concurrent births. This was my journey with the #LoveWITHAccountability forum. This forum was hardcore work for many of the contributors to share their truths about what happened to them as children, and to also share their visions for a world free from sexual violence against children and adults in a public forum.

The #LoveWITHAccountability forum is a continuation of work that precedes this collaborative project, and it is also a beginning. As diverse as the forum is, I am clear that there is always room for more diversity. It is twenty-nine drops in the vast child sexual abuse ocean, which is not to take away from the individual and collective power of those profound drops. Every drop plays an important role in creating the waves of seismic change. It’s extremely important for me to acknowledge that there are additional marginalized voices from within the diasporic Black community that aren’t featured in this forum. This is a beginning.

Up until it was time to publish the articles and poems, I was a one-woman entity. This was intentional by my design and it has taken its toll. I thought I was going into the very deep end of the pool with this forum. Instead, I found myself in the middle of an ocean of trauma. Fortunately, I had many resources in the form of twenty-four years work with Dr. Clara Whaley-Perkins, a Black feminist licensed clinical psychologist and founder of the Life After Trauma Organization, a fourteen year practice of vipassana meditation, and a trusted inner circle of sister-sibling-brother friends during this process including Mia Mingus, Jennye Patterson, Heba Nimr, C. Nicole Mason, Marie Ali, Josslyn Luckett, Heidi R. Lewis, Tamura Lomax, Luz Marquez-Benbow, Mari Morales-Williams, Nikki Harmon, Yvonne M. Jones, Kai M. Green, Sonja Ebron, Evelyne Laurent-Perrault, Jonathan Crowley, and Molly Broeder Harris. Even with all of human and spiritual resources, there were several times when my head went under the water. I didn’t drown because of the support of resources. The waters are calm for now. I hope I can mentally and emotionally rest a while before the ferocious waves return because they will return. This is the nature of personally and professionally tackling child sexual abuse as an adult survivor. There are so many layers of residual trauma.

It took a village to make this forum a reality. I want to share gratitude for many individuals who directly and indirectly made this forum a reality. The #LoveWITHAccountabilty project probably would not exist without the support of the Just Beginnings Collaborative (JBC). I do not believe I could psychologically and emotionally focus on child sexual abuse day in and day out while simultaneously doing other non-related work to financially sustain me. JBC’s founding executive director Monique Hoeflinger was an important source of unwavering support during both the incubation period and the literal launch of both the project and the forum. John L Jackson, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy and Practice (SP2) enthusiastically welcomed me as a Visiting Scholar. His support of me and my work has also been unwavering. Director Susan Sorenson invited me to be an Affiliated Scholar at the Evelyn Jacobs Ortner Center on Family Violence, which affords me the gift of an opportunity to engage with graduate and undergraduate students whose research and scholarship is focused on addressing various forms of family violence.

All of the JBC individual fellows and two organizational grantees came together in the first quarter of 2016 and formed an ad-hoc collectively defined #SurvivorUnion. We worked together to support each other both in response to an organizational crisis and with our individual projects, which focused on addressing and ending child sexual abuse. It hasn’t always been a crystal stair amongst us, and I am profoundly grateful for the community that we, Mia Mingus (Living Bridges Project),Luz Marquez-Benbow (Love in Sister/Brotherhood), Amita Swadhin (Mirror Memoirs), sujatha baliga(Impact Justice), Tashmica Torok (Firecracker Foundation), Sonya Shah (Project Ahimsa), Ignacio G. Rivera (The Heal Project), Ahmad Greene-Hayes (Children of Combahee), and Aqeela Sherrills co-created. I can’t imagine this journey without their presence, friendship, camaraderie, and support. Each of these individuals are doing incredible ground-breaking work to pull up the roots of child sexual abuse in marginalized communities. I continue to learn so much from them and their work, which inspires my own.

During the first six months of 2016, I had the amazing opportunity to be the Sterling Brown Visiting Professor of Africana Studies at Williams College. My Africana Studies colleagues Rhon Manigault-Bryant and James Manigault-Bryant invited me to Williams College and quickly became my friends and spirit family. It is because of them that I was very fortunate to work with my former student and research assistant Aunrika Tucker-Shabazz. In addition to Rhon and James, I also created a really important close-knit community with VaNatta S. Ford, Rob White, Sophie Saint-Just and Daniel Goudrouffe, Rashida Braggs, Will Rawls, Meg Bossong, Ferentz Lafargue, Vivian Huang, Merída Rua, Amal Eqeiq and Anicia Timberlake. I was able to share my work in process with each of them, and I also shared a lot of much-needed laughter and fun times with them in the metropolis known as Williamstown, MA.

I cannot think of any other online publication other than The Feminist Wire (TFW) where I would’ve been able to publish over twenty-five essays, reflections, poems on child sexual abuse, healing, and justice in diasporic Black communities for ten days. These pieces ranged from 700 to almost 4000 words. Since its co-founding by Tamura Lomax and Hortense Spillers in January 2010 and subsequent leadership by Tamura and her co-managing editors Monica J. Casper and Darnell L. Moore, TFW has always gone deep beneath the surface with our work, most especially our online forums.

Since 2012, TFW has conducted multiple forums, allowing our readers to delve deep with TFW collective members and other writers on a wide range of topics, including, but not limited to: Palestine; Women’s Filmmakers; Muslim Feminisms; Voting; Violence; Black (Academic) Women’s Health; World AIDS Day; Masculinities; Race, Racism, and Anti-Racism within Feminism;Assata Shakur and the Black Radical Tradition; the Aftermath of the (George Zimmerman) Trial;Feminist Theory: A College Forum, Love As A Radical Act; Disabilities; Mass Incarceration and the Prison-Industrial Complex in honor of and featuring Mumia Abu-Jamal; Audre Lorde; Toni Cade Bambara; Climate Change and Feminist Environmentalisms; Campus Violence, Resistance, and Strategies for Survival; Shout Your Abortion; and June Jordan. The #LoveWITHAccountability forum is a part of TFW’s radical continuum.

There are very few, if any, online publications that provide the in-depth left of center, radical, multi-racial, pro-reproductive justice, pro-LGBTQ, anti-imperialist, anti-white supremacist feminist writings that The Feminist Wire has consistently provided for free. This volunteer work of curating, writing, editing, and publishing is almost always completed in our second and third shifts after working jobs, partnering, parenting, and/or, for many of us, being engaged activists for social change in our societies and in the world. I did not call upon support from my dear TFW comrades-friends until it was time to publish the forum because this was the first time that, thanks to funding received from the Just Beginnings Collaborative, I could solely focus on the forum work all day and every day. With that shared, Heather Turcotte, Tamura Lomax, Heidi R. Lewis, Heather Laine Talley, Monica J. Casper, TC Tolbert, Joe Osmundson, and TFW’s Editorial Interns Jazlynn Andrews and Angela Kong each played important roles with the publication of the forum. There’s the literal work of uploading, copy editing, resizing of photos, tagging, and hyperlinking. Then there are the personal extended texts, emails, and voicemail messages to check in and consistently send love and emotional support along the way that underscores the TFW community building that many of us work hard to sustain through the cyberwaves in the midst of it all.

My sister-friend C. Nicole Mason reminded me that I do not walk on water and my well-being would be at stake if I tried to do everything including promoting the forum. She connected me with two incredible Black women who helped me with creating the visuals for my work. Kathryn Bowser created the gorgeous #LoveWITHAccountability logos. Maura Chanz and her company Glitter and Hustle handled all of #LoveWITHAccountability’s social media sites. She created the beautiful images that brought some of Aunrika’s research to visual life. Maura also lifted excerpts from each of the contributors’ words to create beautiful collages with their images. The website was designed by my dear friend Jennifer Patterson who five years ago played a pivotal role with igniting my journey to address my own child sexual abuse.

Sister Valerie Ann Johnson invited me to participate in the Africana Women’s Studies’ inaugural “Heal the Healer” week-long residency at Bennett College. The residency unexpectedly coincided with the second week of the forum, which turned out to be a gift. My time at Bennett College was a much needed respite in the company of sistren, and for that I am most appreciative.

There aren’t any words that will articulate the depth of my deep gratitude and love for each of the individual twenty-nine #LoveWITHAccountability forum contributors who trusted me enough to take this public journey with me. It wasn’t easy for most of the contributors. Everyone’s plates were already full and yet, they accepted my invitation to revisit excruciatingly painful experiences in their lives and envision what accountability for child sexual abuse can look like. Despite my huge ask without a lot of time to reflect, re-member, process, write, and publicly share, they pushed through to participate. Their commitment to this forum is powerful commentary on their unanimity that we must break the silence and address child sexual violence in our diasporic communities.

The forum contents are listed below in chronological order. There are over twenty-five individual archived road maps from which readers can explore and decide which routes, if any, resonate with part of their journeys.

The movement to end child sexual abuse is not a one size fits all movement. #LoveWITHAccountability is a call to action that doesn’t end with this forum, as there are many more road maps in multiple communities.

**********

Publication Timeline for #LoveWITHAccountability forum:

- Aishah Shahidah Simmons, Digging Up the Roots: An Introduction to the #LoveWITHAccountability Forum

- Chevara Orrin, Soul Survivor: Reimagining Legacy

- Danielle Lee Moss, Ed.D, Love Centered Accountability

- Aunrika Tucker-Shabazz, How I Built Community While Researching Accountability

- Ahmad Greene-Hayes, “The Least of These”: Black Children, Sexual Abuse, and Theological Malpractice

- Kai M. Green, Ph.D., Fast

- e nina jay, a place to live

- Thema Bryant-Davis, Ph.D., Our Silence Will Not Save Us: Considering Survivors and Abusers

- Adenike A. Harris and Peter J. Harris, [VIDEO] Pops’nAde: a Courageous Daughter & Her NonAbusive Father on Loving Lessons, Living Legacies (L)earned after Sexual Violence

- Worokya Duncan, Ed.D., Unfinished

- Zoe Flowers, Violation and Making The Road By Walking It

- Ignacio G. Rivera, Accountability to Ourselves and Our Children

- Tashmica Torok, Casting Aspersions

- Cyree Jarelle Johnson, Social Silence & Child Sexual Abuse

- Alicia Sanchez Gill, A Network of Care

- MiKeiya Morrow, We need Speak7 because Black Children Matter and Child Sexual Abuse Thrives in Silence!

- Liz S. Alexander, In My Mother’s Name: Restorative Justice for Survivors of Incest

- Tonya Lovelace Sunset: Seeking True Accountability After All of These Years

- Nicole Mason, Ph.D., Oh, to Be Free Again: Love, Accountability & Bodily Integrity in Response to Child Sexual Abuse

- Sikivu Hutchinson, Ph.D., The Coiled Spring First Grader Deep Inside: Sexual Violence and Restorative Justice

- Cecelia Falls, Self Love with Accountability

- Loretta J. Ross, Paying it Forward Instead of Looking Backwards

- Qui Dorian Alexander, Thoughts on Discipline, Justice, Love and Accountability: Redefining Words to Reimagine Our Realities

- Kimberly Gaubault, Safe Space: The Language of Love

- Thea Matthews, activist, poet, prison abolitionist, human rights advocate, incest and rape survivor

- Kebo Drew, It's the Whispers

- Ferentz Lafargue, Ph.D., On Moving Forward

- Luz Marquez-Benbow, Who is Accountable to the Black Latinx Child?

- Lynn Roberts, Ph.D., Becoming Each Other’s Harvest

- Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, Ph.D., with Aishah Shahidah Simmons, LOVE WITH ACCOUNTABILITY: A Mother's Lament & A Daughter's Postscript

- Aishah Shahidah Simmons, "It Takes A Village": the Afterword to the #LoveWITHAccountability forum

May we all envision and work diligently to co-create a world without violence for the future generations…

Photo Credit: Daniel Goudrouffe

Aishah Shahidah Simmons is a Black feminist lesbian incest and rape survivor, award-winning documentary filmmaker, published writer, international lecturer, and activist. She is a Just Beginnings Collaborative Fellow, and a Visiting Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy and Practice, where she is also affiliated with the Evelyn Jacobs Ortner Center on Family Violence. She is the creator of the film NO! The Rape Documentary and the #LoveWITHAccountability project. An associate editor of The Feminist Wire, Aishah has screened her work, guest lectured, and facilitated workshops and dialogues to racially and ethnically diverse audiences at colleges and universities, high schools, conferences, international film festivals, rape crisis centers, battered women shelters, community centers, juvenile correctional facilities, and government sponsored events across the United States and Canada, throughout Italy, in South Africa, France, England, Croatia, Hungary, The Netherlands, Mexico, Kenya, Malaysia, India, Switzerland, St. Croix U.S.V.I, Germany, and Cuba. You can follow both #LoveWITHAccountability and Aishah on twitter @loveaccountably and @Afrolez.